Chimera

Thanks for reading Dispatches. A warm welcome to newcomers!

EVERY ONCE IN AWHILE a film does its own complex things well, yet also summons unexpected memories and connections. Some investigations. A spate of marvelling. Perhaps a drawing or two. This is how it’s gone down for me, thanks to the intriguing La Chimera, dir. Alice Rohrwacher (2024), recommended by my friend Kris.

The chimera consorts with my here-and-now, and also with my present state of mind and body as I slip back into the past and skid back into teaching and university people and surroundings.

The chimera (or chimaera) was imaginary, much better than real. Fire-breathing, with a lion’s head, a goat’s body and a serpentine tail, she was said to lurk and threaten from her distant land. Many-headedly monstrous, hybridic and initially confounding, she posed a thrilling threat and remained visionary-wondrous in her possibilities.

But how completely the chimera, for most people, has tripped out of the embodied imaginaries of ancient Greek mythology and into the further margins of figurative language. Chimera now signifies not just wild fancy, but mere wild fancy. The overspilling site of menace and wonder flips into a word for unchecked imagination. A foolish and vain thing desired, hankered after, but quite impossible to achieve. A figment, an unrealistic notion, beyond the edge of the edge. To be chimeric or chimerical is to have lost the plot, grown prone to over-indulgence in oneself and one’s own crazy, crazy chimeras, fanciful dreams rather than realisable schemes. To entertain the inherently improbable is to chimerise.

◇◇◇

I first encountered the Chimera in September, 1982. Almost exactly forty-two years ago. The lecture hall —just off the central campus plaza at the University of Alberta (where I’d been illegally guzzling beer with everyone else the day before)— seemed glorious to seventeen-year-old me. Cavernous, semi-dark, and frightening, but also just how the setting for a first class, on a first morning, at any university should be.

I was someone looking for something, and in this respect may not have changed very much in the intervening years.

Way up at the front, back there in Edmonton —past my cup of coffee and what seemed an impossible number of attractive women— was a tall black man behind a lectern. From a pool of light, just there, he would show slides, often his own photographs of magically-named places, and objects in far-off museums. Bespectacled, be-necktied, he unleashed an extraordinarily-paced west African-Oxford English voice, while seeming to move only his face and arms. He radiated a kind of self-assuredness and learned integrity I’d never encountered before. I couldn’t imagine speaking with him one on one. He issued a string of challenges from the front of the hall, to anyone who was listening. Three mornings a week that autumn, he stung and nipped at us, his words differently arrayed than other people's words, conjuring wonder, coaxing something in us that I now understand to have been a confident kind of humility.

“Keep your wits about you,” he warned with the hint of a smile. The likes of me had barely let go of mama’s apron strings and here was this astonishing person, addressing us as interpretative allies, as if we were his worthiest peers. Warning us about how crafty we’d surely find this Ancient Greek person called Homer to be.

“His kind of poetry was performed,” he offered, “and so it meanders, from moment to moment,” Professor Kweku Arku Garbrah1 suggested. “He can sometimes seem to be hiding his best material.”

Homer’s nested tales aren’t just digressions, or throat-clearings, or warm-up acts, he explained. They layer on, they deepen. They craft slow, artfully condensed rewards for an attentive listener, purposes that are only revealed in time. A character’s motivations appear in all their terror and glory through these stories. Personages, precedents and patterns gradually take root in the listener’s mind. Sub-plots enter the enchanted garden, while a purported main plot —lovingly recalled, probed— branches and thickens, nurturing through story the ideal conditions for the most powerful and sustaining of all qualities in a human being: anticipation, passion, excitement.

“In our rush towards the exploits of the latest Perseus or Heracles on our horizon, towards the ‘greatest hits,’ some of the most compelling stuff —in Homer as in life— lies unappreciated, and unconnected,” the Kweku Garbrah-of-my-memory sighed. “So, off you go! This weekend, find an embedded story in The Iliad, the one which most perplexes you! Why-in-the-world does it exist?,” I think he continued (in what I later learned was a “rhetorical” move), “why was this adventure included? Why did Homer tell the tale thus, in such detail, and just there and then, when, surely, listeners were fidgeting and a return to the larger story beckoned?”

“Then, come back to class with an explanation of what drew you in. I’ll ask a random few of you to tell us why: why did you choose this interpolated story?”

I can’t have been the only seventeen-year-old from Classics 102 who, clutching my Penguin translation of Homer that same afternoon, scurried over to one of the big dictionaries on their old wooden lecterns in the reference room in Rutherford Library, and looked up “interpolation.”

◇◇◇

BOOK SIX OF The Iliad was jam-packed with adventures.2

Bellerophon —son of Glaucus, grandson of Sisyphus— departs Corinth “under a cloud” of murder and misdeeds.3 A sharp and incomparably handsome youth, he takes refuge in the kingdom of Proteus of Tiryns, where he soon draws the amorous attention of Proteus’s wife Anteia. She begs Bellerophon “to satisfy her passion in secret,” and then takes the visitor’s refusals poorly, reporting to her husband that this Bellerophon has tried to seduce her. Believing the queen’s accusation without further investigation proves easier for Proteus than facing what may have been the writing on the wall. He exiles Bellerophon to Lycia, kingdom of his brother-in-law Iobates, bearing a folded tablet, about which the gods also learn. “Pray remove the bearer from this world,” the tablet instructs Iobates in code.

This king of Lycia proves no less a proponent of the indirect penalty than Proteus had been. Iobates comes up with a series of services for Bellerophon to perform, several surely impossible challenges to face. Not the least of them is to find and exterminate a ferocious monster known as the Chimera, “a creature whom the gods had foisted on mankind,” that was said to launch her attacks from the realms of Iobates’ rival, the King of Caria.

Bellerophon takes counsel. After wincing at the immensity of the mission, the seer Polyeidus opines that the young wanderer could use some help. Enlisting the help of the winged horse Pegasus would hardly go amiss. Here accounts differ: Pegasus is either found and tamed while drinking from the well or he is golden-bridled and gifted to Bellerophon by Athene herself. Either way, the gods are even more closely tuned in as our tainted hero sets off on quite a mount.

The Chimera —three-headed and expelling “terrible blasts of burning flame”— is no push over.

The Chimera only begins to be overcome when our adventure-pair —Bellerophon astride Pegasus—fly up and overhead, raining down arrows upon her. But it’s still not nearly enough to fell the now enraged monster. Desperate battles ensue, one of which may have seen a dismounted Bellerophon, reins in hand, spearing at the fearsome Chimera’s belly while the rearing Pegasus joins the assault, pummelling their opponent’s neck and chest with his hooves.

Only when Bellerophon faces the monster head on —fixing a chunk of lead to his spear point and ramming it down the Chimera’s throat— do the pair’s fortunes brighten. It’s a winning plan. The beast’s scorching breath melts the lead, which trickles down and inside, searing her organs and beginning to harden. This is how the Chimera meets her end.

As for Bellerophon and Pegasus, their stories are not quite over. And while they happen to untwin, both figures spin into symbolism and association, as does the Chimera’s.

Iobates cannot fail to be impressed by Bellerophon, but the crushing of the Chimera soon fades from the ruler's mind.

He's slow to trust the dashing visitor, preferring to insist on another test, and then another and another, one of which is surely to be this cad’s demise. Only when the victories mount does the king deign to show Bellerophon the tablet prompting his account of what did and didn’t happen behind Proteus’s back. King Iobates’s tearful apologies, an offer of his daughter’s hand in marriage and the smoothest succession to the Lycian throne for Bellerophon ensue.

You’d have thought that our protagonist would’ve rested, and known better. That he’d think upon his own murky past, his misdeeds, his profitting from fame, his weaknesses along the way, his doubts, his foibles, his regrets . . . .

But success goes to Bellerophon’s head. He wagers it's past time to join the gods atop Mount Olympus, and prepares Pegagus for the presumptuous flight. What’s meant to be a triumphal ascent comes up dramatically short. Zeus will have none of this —this latest human pretender— and dispatches a gadfly to bite Pegasus’s backside, causing the mighty winged steed to rear up and lose his rider. Bellerophon plunges back to earth. Gathering himself, ignobly from a thorn bush, he ends as one who “wanders the earth,” a shadow of his former self, writes Robert Graves, “lame, blind, lonely and accursed, always avoiding the paths of men, until death overtook him.”4 It’s not for nothing that over time Bellerophon has come to signify the aftermath of promise, suffering, excessive black bile, a psychopathological fusion of genius and sadness, complete melancholy.5

◇◇◇

As for winged Pegasus, said to have sprung (along with Chrysaor) from the unfortunate head of Medusa —as for the “poet-horse” who came to symbolise “the flight of thoughts” and even the necessarily lonesome path to truth — well, what’s your reading of Pegasus’s various fates, his meanings. After losing Bellerophon for his back, he continues on, flying solo to the Olympian heights.

He comes into the employ of Zeus himself, a “servant-animal” consigned to bear the god’s lightning and thunderbolts forevermore.6 Or do you favour Pegasus’s becoming a heavenly constellation, up there between Andromeda and Aquarius?

Or the fact that “Pegasus” has —by now, across a vast diaspora— become the favoured name of not a few Greek restaurants?

As with the Chimera —as with the interpolated story I wasn’t called upon in class to tell all those years ago— as with the Chimera, it just depends what you end up looking for?

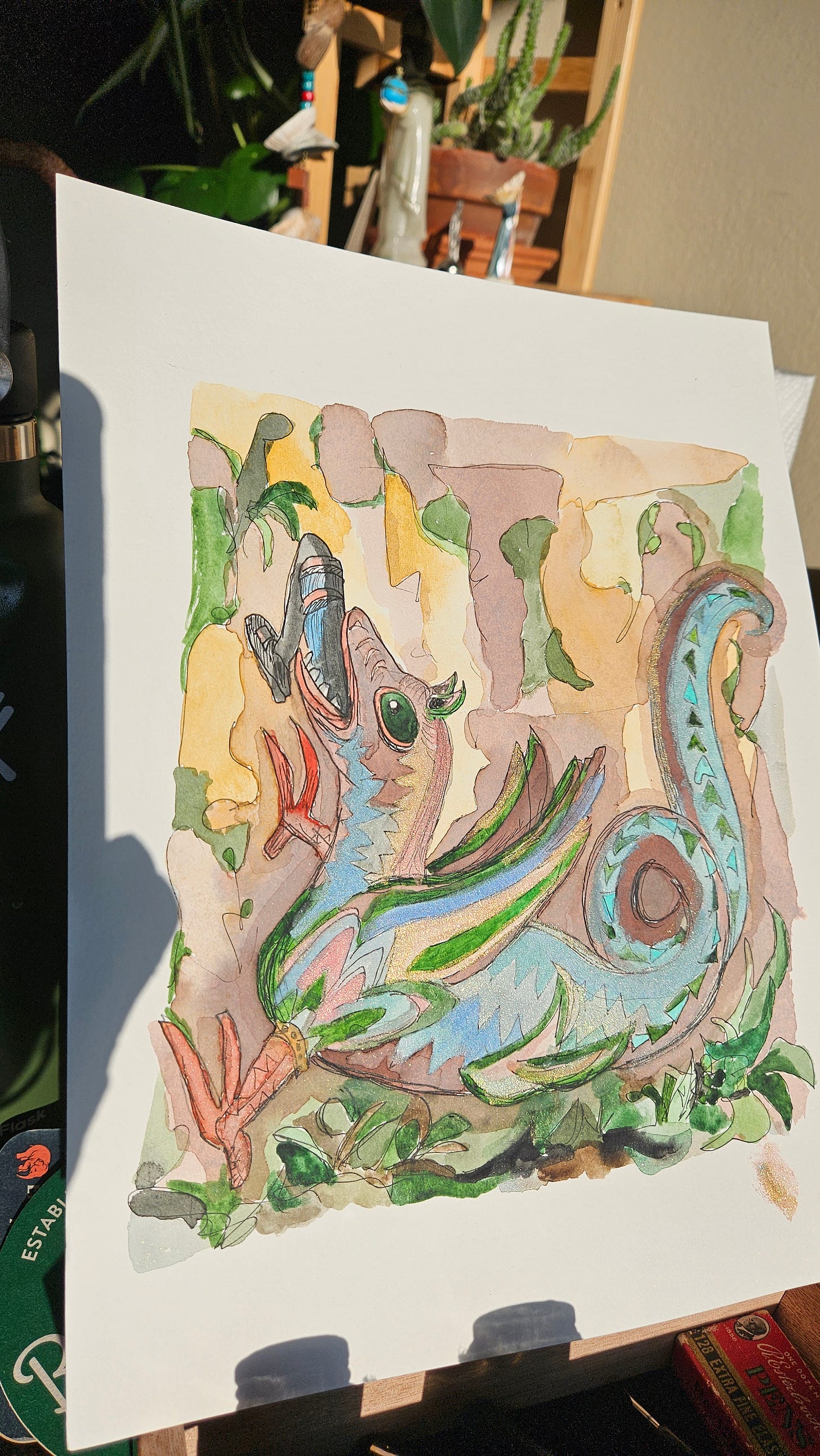

* watercolours and photographs by Kenneth Mills unless otherwise indicated.

** special thanks to Kris Lane (for the film recommendation), Heidi V. Scott (who has been party to ongoing Chimera investigations), and David C. Johnson.

Kweku Garbrah (1937-2014) was born in Cape Coast, Ghana, studied at the University of Ghana, Legon, before earning an external Bachelor of Arts at the University of London, from which he went up to Oxford (B.Litt.) and on to the University of Cologne (D. Phil.) Described by Anna Moyer as an exacting teacher, “a consummate philologist,” Garbrah’s expertise lay in interpreting Ancient Greek texts, defining grammatical, syntactical and dialectical variants. Garbrah taught at several institutions in North America before settling in at the University of Alberta, where he taught from 1972 until 1990, rising through the ranks, before following up on a visiting professorship at the University of Michigan with a full appointment there. He taught in Ann Arbor for twenty-five years. Garbrah died in October 2014, a little less than a year before I happened to come to the University of Michigan. See the aforementioned obituary by Anna Moyer, from which I draw. In response to my queries about the name of an unforgettable Classics professor back in Edmonton in the early 1980s, it was my first teacher of Latin American history, David C. Johnson who came to the rescue. With the help of Jeremy Rossiter, David discovered Garbrah’s name, trajectory and destination. “A kind of transmigration of souls,” he said.

Unless otherwise indicated, quotations from the translation by E. V. Rieu, Homer, The Iliad (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1950), book VI: esp. 160-176, or pp. 117-131, esp. 121-122,

Robert Graves, The Greek Myths (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, revised ed. 1960), vol. 1 [of 2], 252. See section 75.

Robert Graves, The Greek Myths, vol. I, 254

Thomas Rütten, translated by Deborah Lucas Schneider, “Melancholy” in The Classical Tradition, eds. Anthony Grafton, Glenn W. Most, and Salvatore Settis (Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard Universioty Press, 2010), 579-581.

Marcy Norton, The Tame and the Wild: People and Animals after 1492 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2024), 64-68.

I am glad you are back in your storytelling and memoir voice. I recall your early boyhood story when I first came across Dispatches, and the elegy of your Cambridge mentor, and think you are building your own memoir tale by tale. What a wonderful gift for Kweku Arku Garbrah to listen down upon.

Love the watercolor. Love the audio. And I love how this takes us back to the young man awakening to all that literature can offer.

Great post, my friend.