Prelude.

This dispatch has a complement, following the lead of an esteemed Substackian colleague

—whose writerly unfoldings in are highly recommended.I rather like what I take to be

’s way of choosing and dispersing a single note (a passage, an idea, or an actual “footnote”) for all and sundry. So, I have selected a single “note” (actually a caption to one of my photographs) from what follows, to share with readers via the platform: think of it as a special point of entry, and a teaser towards the substack post, in this case “Dublin, Lavinia Fontana, and the Queen of Sheba.”If this move pleases in some way, I promise to refine my practice. And maybe also to record an audio complement to what I’m up to, another

thing.Thanks so much for reading Dispatches (and perhaps even imbibing some dulcet western Canadian tones), and I hope you enjoy the return journey to Ireland,

k.

🎶

I WAS IN Dublin last week, for only the second time (cf. Dublin [I]). And it felt like a return, the resumption of a journey, of the meditations that this place invites.

I met up with Heidi, and with some dear friends. We stayed in a venerable neighbourhood north of the river called Stoneybatter. And I was there to do a bit of work —up to which I will sidle in due course— and … to take things in.

Not just to take in the wooden pubs and old-school courtesy . . .

I was there for more, too, than the glowing cosy snugs,

all the warm and characterful people and pups,

on richly upholstered seats, and surrounded by stained glass,

as insistent as the changeable skies, as all the playing out of darkness and light.

I was there for more than libation, though the culture of drink and atmosphere, and the moments they proffer, entice,

and are an aspect of a broad Irish genius. For slowing down, for pausing. To think. To talk. And, not infrequently in Dublin, to be talked at,

I was there for more than my mornings with books and research libraries, too.

For more than (what soon became the unexpectedness of) sunshine, those bursts of that light.

Bringing everything —the medley of ironwork and brick, the divine rows of chimney pots, the odd angles and walls, the dabbles of geranium— bringing every damned thing to life.

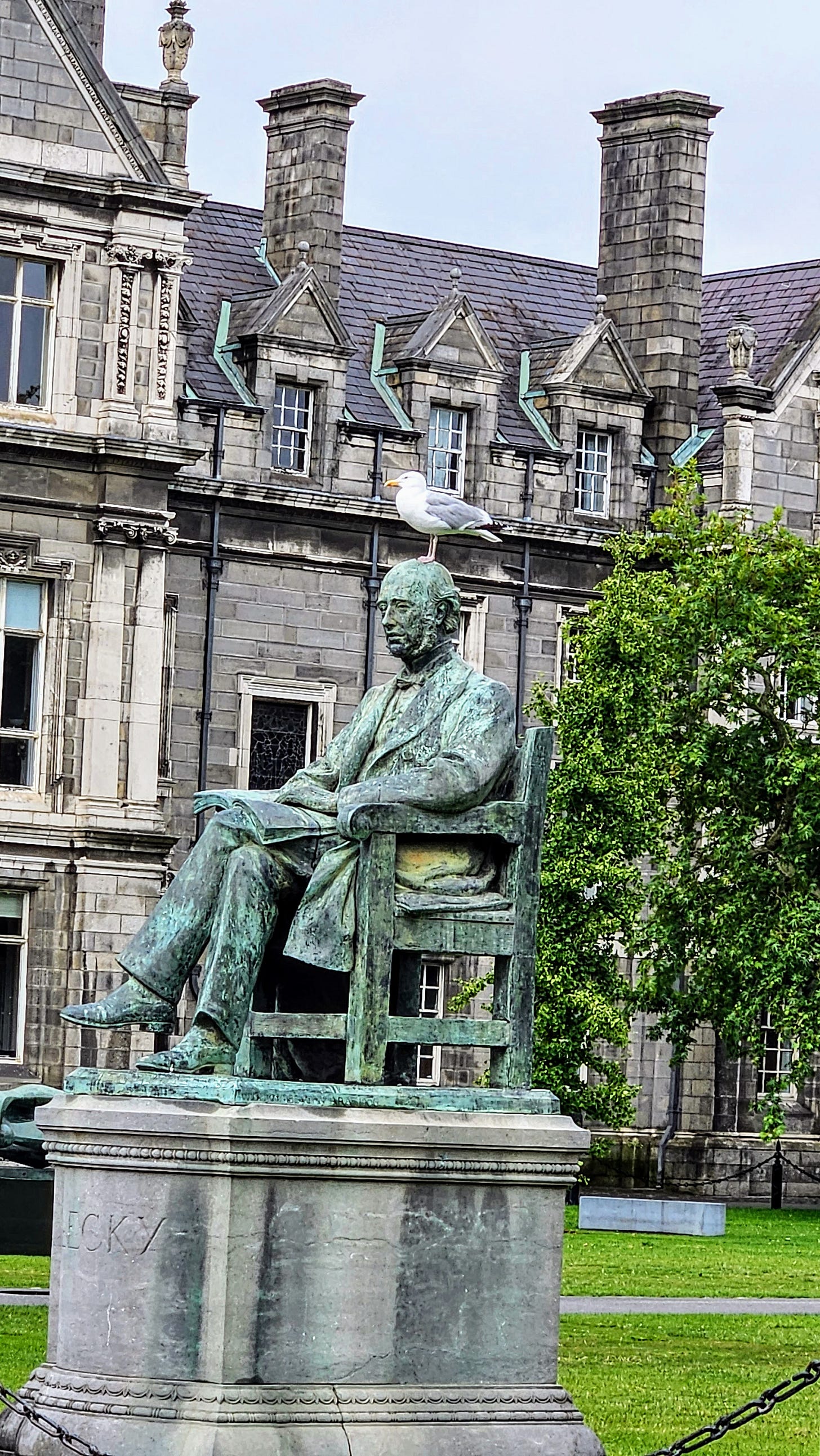

I had come for a certain reacquaintance,

a reacquaintance with the ways in which

Dublin dazzles amidst life’s drizzle.

◇◇◇

I WAS IN Dublin to see an exhibition of the paintings of Lavinia Fontana (1552-1614).

Well-educated, with a degree from the University of Bologna, where she went on to teach, Fontana was trained in painting by her evidently indefatigable father Prospero and another, Ludovico Caracci. Word of her extraordinary talent was soon out. Already by 1579, she had been commissioned by the Spanish Dominican theologian Alfonso Chacón, then residing in Rome, to create a small self-portrait.

She executed an arresting work in oils on copper. Gazing out at the viewer, she’s an artist, but also the consummate scholar and collector at her working table; she’s a humanist in elegant dress, with a lacey ruff and just enough piety: a heavy golden cross hangs from a necklace of pearls.

She’s poised with pen and ink before a blank page: either to write, or perhaps to sketch one of the figures or casts arrayed before her and on the shelves behind. She is, and appears, more than capable of both, and of so much more. What seems to matter —and what doubtless drew the attention of Chacón and his like— is the assertion of her intelligence, her confidence, and mastery over classical sources of inspiration.1

Given how much Lavinia Fontana had seen of life and death (only three of her eleven children would outlive her2), and given the evidence of her humanistic endeavours and how comprehensively she blasted past artistic confinement to “female topics”3 —to subjects deemed acceptable for late sixteenth-century Italian women (even highly educated ones)— she strikes me as an artist a little too commonly and monochromatically celebrated as the first female to study and render the nude human form in painting. Her allegorical play, her portrayals of beauty, drawn from an immersion in nature and a learnedness before the vast emblematic sources and “medieval mythographies” of her day, offer delicious complexity.4

By 1604, she had left Bologna for Rome. News had spread further of her talent for expressive portraiture, and, moreover, of her invenzioni. Her work’s complex allusions to, and ingenious interpretations of classical mythology and Biblical themes may not have won her the lucrative altarpieces she deserved, but she collected significant admirers. Her circle of patrons grew quickly among the wealthy and well-connected, and soon included a string of popes. Lavinia Fontana became the first woman accepted into the Roman Accademia di San Luca. Her portrait on the front of a commemorative medal (the back of which features a wild-haired “allegory of Painting”) from 1611, when she was aged fifty-eight, has been read as a record of her intellectual and artistic navigations, of her remarkable freedoms and triumphs.5

In the National Gallery’s exhibition, the work which (for me) steals the show resides in Dublin’s own collection: it’s rightly saved for this journey’s final room.

The Visit of the Queen of Sheba to King Solomon (1599; or 1598-1600) is more than Fontana’s rendering of an alluring Bible story6 that would soon enjoy wider resonance. Drawing on the research of Luigi Lanza and Eleanor Tufts, Caroline Murphy explores the canvas as an allegorical portrayal of a visit made by the Duke and Duchess of Mantua —members of the noble Gonzaga family (en route to a Medici wedding)— to the home of Ercole dall’Armi, a well-connected papal treasurer resident in Bologna. Dall’Armi’s family, looking to commemorate the choice of their home as these dignitaries’ staging post, likely commissioned the work. The painting simultaneously honours a crucial constituency for Fontana and her work, the well-to-do “ladies of Bologna,” who appear here as the Queen of Sheba’s eye-catching retinue.7

Murphy characterises The Visit as one of Fontana’s most difficult challenges; “compositionally,” Murphy explains, “there are a number of problems with the picture, most notably the relationship between the women’s heads and bodies.”8 While one fast understands what Murphy means, both Heidi and I found the effect of the painting immediately and utterly spellbinding, not least because of the ladies-in-waiting, whose heads might differently be said to be magnificently rendered, set to look about so variously, so curiously, as if floating atop their carefully contemporary dress and fancy ruffs. Drawing the eye away from the gifts of jewels and gold in their hands, and from even so lavish a room.

The canvas is large (256 X 325 cm), and while a Latin inscription on the lowest step up to the king’s throne suggests a cleaving to the main thrust of the biblical story (“The Queen of Sheba came to Jerusalem in order that she might test Solomon with difficult questions, and she gave him many great gifts”9), there is arguably much more to see.

The eyes of the arriving Sheba figure, in her exquisite dress, and of the wise King Solomon, on his canopied throne, are locked, to the canvas’s left. A solemn gaggle of formally-dressed men peer upon the scene from the shadows just behind. Still left, in the immediate foreground, an attendant, seen from behind and mostly-obscured, steadies a powerful sword. Much cries out for the “pictorially central role” to be played by the Queen of Sheba,10 but with the ladies-in-waiting inseparable, standing back a step and arrayed on a slightly higher plane than their queen, who is about to kneel.

But my experience of the painting in Dublin is that Fontana draws the viewer’s eye decidedly away from the ostensible subject, away from the forgettable Solomon and even from the extraordinary Sheba —away from this iridescently embroidered power-pair, then— further and further to the right. The aforementioned heads of the Bolognese noblewomen first command attention, and especially one woman —front and centre in this tight assembly— perhaps it’s someone who sat for Fontana, a friend or patron or godmother to one of her children, or perhaps it’s an actual visitor to the dall’Armi from the Italian house of Mantua being remembered here.

A courtly dwarf —perhaps it’s a man named “Stefano” who was among Vincenzo Gonzalo’s contemporary entourage of entertainers11 — strides forward. He fingers the pearls at her hip, while —with a sweeping gesture that's followed by the woman’s gaze— he indicates an approaching attendant. This servant of African descent is almost certainly enslaved; elegantly moustachioed, with a fine headband, and gazing ahead, he barely enters the scene. But on his silver tray Fontana places things to ponder. There’s a bejewelled, metal animal’s head, for starters, a casing “in which would be set the head of a marten or sable or other member of the weasel family,” the pelts of which, Murphy informs, often hung from chains on the girdles of women in contemporary portraits. While these common “fertility charms” for brides-to-be would have been recognised by Bolognese viewers and perhaps even connected to the purpose of the Gonzaga family’s actual journey, it’s an odd gift to be conveyed into Solomon’s court by the Queen of Sheba. “Hardly an appropriate item,” observes Murphy, before moving on to its contemporary resonance. 12

What if we add to our considerations the fine golden vessel overturned on the tray, the disarray, the upset of order?

Just a recognisable marker of plenty’s overspill, of a showy nobility's conspicuous consumption in each other’s presence— and at the same time the toppling complements to the jewels, precious stones, exquisite spices, and camels said in the Bible to have been brought to Solomon by the queen's retinue?

Or is something “wrong,” with tension and trouble afoot? Might Fontana’s investigations have alighted upon a mediaeval reconstruction of the story of the visit of the Queen of Sheba to Solomon, one in which a far more complex diplomatic and charismatic struggle between the pair —between rivals, and potential sexual and marriage partners— comes into play?13

If there’s more to notice, Fontana has arguably put her signals in the hands of the dwarf and the servant, and in the alertness of the hunting dog, whose ears prick up and muscles ripple. The amazing retinue of women is dressed to impress, and they’ll both give and receive elaborate gifts in an exchange with their powerful hosts. As for the Queen of Sheba, she best watch her step.

◇◇◇

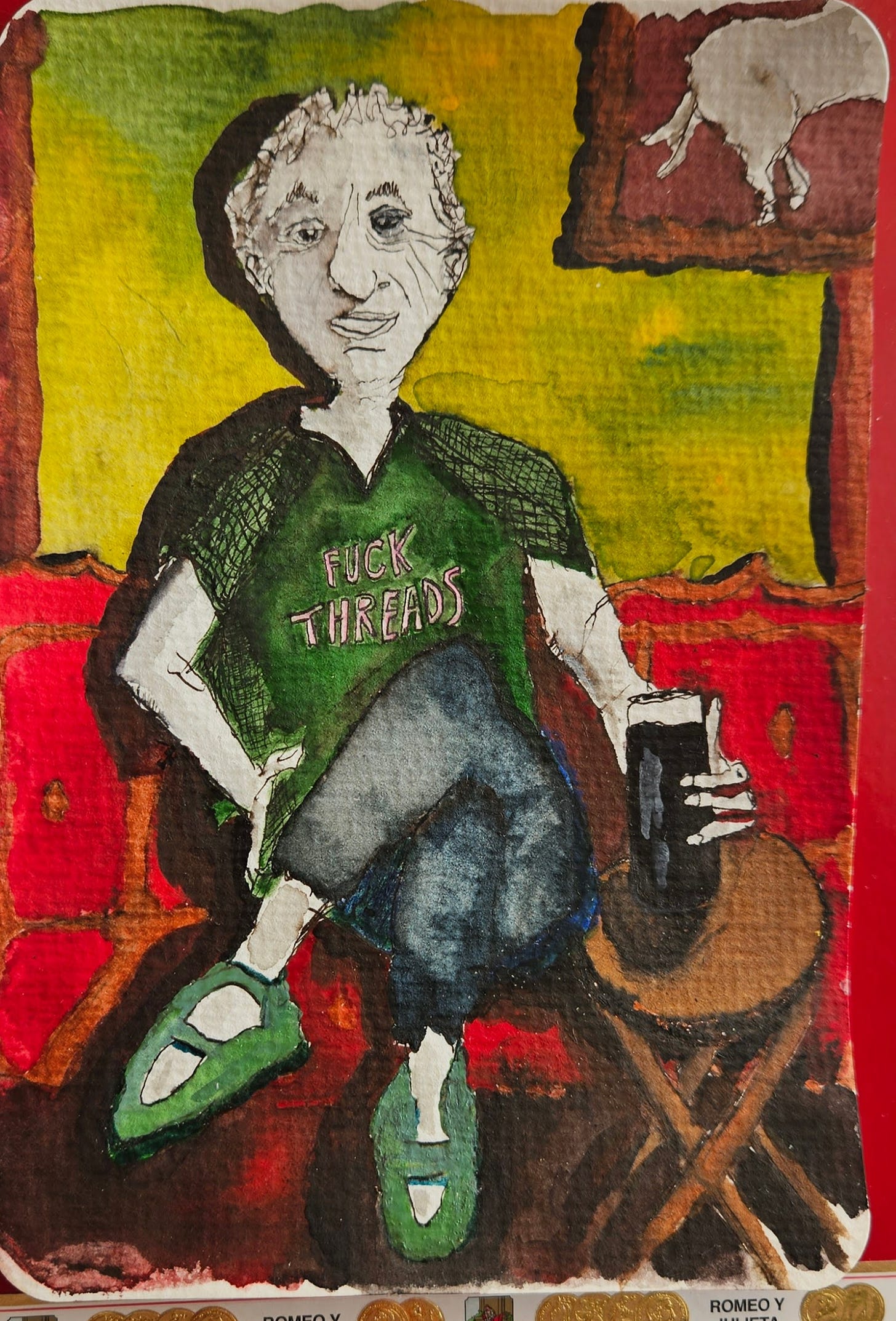

BACK IN GROGAN'S, regulars rule the best spots, the commanding vantages. They hold forth in welcome of the likes of me, a scruffier kind of visitor than King Solomon or Ercole Dall’Armi ever received. And yet the common currency, across time and space and language, is story.

I meet a local sculptor named Kevin Gaines (I didn’t learn his surname that evening, but, within a day of this substack hitting the street, Jean-François Lozier's resourceful sleuthing fixed that. Click his name and Read an exquisite interview with this wood-wizard). I meet him beneath a stained glass window, the best one yet. It —breathtakingly— immortalises the beloved pub’s interior features, and a number of charismatic barflies very much like himself, habitués (from the late 1980s and early 1990s) of the very same Grogan’s micro-environs in which Kevin and I converse some three decades later.

Kevin tells me of adventures, some from far away but most from within the lore of the pub, long a haven for artists and writers and students.

And he shows me photographs of a few of his pieces. Each picture occasions a story (or three), including the stories who, like ladies-in-waiting for his telling— accompany a piece of African timber he’d fished from a Dublin canal, recognised for its strength and provenance, and then re-fashioned into a kind of soaring, twisting, wooden corkscrew (my description). He hopes that people will stand before it in the Botanic Gardens —near the steps where Ludwig Wittgenstein liked to sit in the late 1940s, Kevin adds— and “find something to think about.” I lament not having had time to seek it out, to follow up his story, and to heed his advice.

Kevin also draws upon an encyclopaedic knowledge of the National Gallery of Ireland’s collections, built up over a half-century of visits that began when he was a child.

Unprompted, in Grogan’s in Dublin city, he tells me about Lavinia Fontana and the Queen of Sheba. How long he’d waited for “Lavinia” to get her due.

* watercolours and photographs by Kenneth Mills. With the exception of the first of Walsh’s pub, which is displayed on the bar’s Facebook page.

** My debt to Caroline P. Murphy’s research is large, as to that of Liana De Girolami Cheney in particular. Errors and over-romanticisations within are all my own. I’m grateful, again, to Megan Holmes, for advice and a generous expert’s leads on how I might prepare to encounter Lavinia Fontana. I am happy —a half-day after “going to press”— to add thanks to Jean-François Lozier, who tracked down the surname (the wood, and a few more stories) of the Dublin sculptor Kevin Gaines.

Liana De Girolami Cheney, “Lavinia Fontana: A Woman Collector of Antiquity,” Aurora. The Journal of the History of Art, vol. II (2001), 25-33; 22-42; Caroline P. Murphy, Lavinia Fontana: A Painter and her Patrons in Sixteenth-Century Bologna (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2003), 73-74;

Murphy, Lavinia Fontana, 182.

Cheney, “Lavinia Fontana: A Woman Collector,” 24.

Liana De Girolami Cheney, Lavinia Fontana’s Mythological Paintings: Art, Beauty, and Wisdom (Newcastle: Cambridge Scholar’s Publishing, 2020), xxi, 3-4.

Emanuele Lugli, “Lavinia Fontana’s Freedom,” Art History 46:2 (2023), 282-309.

2 Chronicles 9; 1 Kings 10.

Murphy, Lavinia Fontana, 106-108; Eleanor Tufts, “A Successful 16th Century Portraitist: Ms. Lavinia Fontana from Bologna,” Art News (February 1974), 60-64; Luigi Lanza, Storia pittorica della Italia (Bassano: 1789), V, 49.

Murphy, Lavinia Fontana, 108.

For the inscription, Murphy, Lavinia Fontana, 106 and 208 n. 77.

Murphy, Lavinia Fontana, 108-109.

Murphy, Lavinia Fontana, 108.

Murphy, Lavinia Fontana, 109.

Shahla Haeri, The Unforgettable Queens of Islam: Succession, Authority, Gender (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020), ch 1: The Queen of Sheba and Her Mighty Throne, part 1: Sacred Sources of Authority: The Qur’an and the Hadith, 29-50.

Ken, a question for a fellow traveler: when you walk into one of these exquisite pubs and spy a perfect seat that seems surprisingly free, you must assume (like me) that it’s been claimed, semi-permanently, by someone more deserving. Do you ask its neighbors, or sit elsewhere and observe, or just plop down? These are the rules of the road, and I’m wondering what yours are..

Where to start with this. What a joy. My parents met in Grogan’s and my cousin lives in Stoneybatter. (I grew up far south of the river, spitting distance to Joyce’s tower actually.) Have you read the mirror and the palette? Fontana features in it, a study of the self-portraits of female artists. A transformative read. I haven’t been back to Dublin in a year but feel a pressing need to go see this exhibit - and visit the Long Room, maybe see the day’s page in the Book. Kenneth, I hope you had decent weather in Dublin. I feel sunnier for having read this so I reckon you must have.