WILLEM BOUWMEESTER —KNOWN as ‘Uli’ from before he can remember— is the creation of Harry Mulisch (1927-2010). The main character in Mulisch’s Last Call (originally published in 1985), Uli is last in a distinguished family line of actors on the Dutch stage. In spite —or, more likely, because of the weight— of his pedigree, Uli showed promise but never quite ‘made it.’

Unless ‘making it’ includes his appetite for mystery, and the way he has retained a sense of his own self and promise.

Unless it allows for how he had scraped by as a variety artiste and director of amateur theatre. Unless making it includes how he’s been widowed from a beloved wife and dachshund named Sebastian, how he’s endured the memory of having performed for his country’s German occupiers during the second world war, and for how he ran an amiably failing bar called The Cellar.

THE READER MEETS an elderly Uli, watching herons and whiling away his time in the polder outside Amsterdam.

He lives with an elder sister Berta, who is as kind as she is nosey about his thoughts. When Uli lingers into the evening in town, he thinks about his sister falling asleep before a television show, “some mindless American serial about rich people . . . the poor woman, the snowflakey black-and-white images flickering on her sagging face.”1

Then one day a letter arrives out of nowhere, offering Uli a role, a considerable challenge.

“You have hauled me out of a very deep well,” he soon confesses to the much younger members of the acting company that, against all odds, has tempted him back onto the stage. Every afternoon the gang of actors drink and eat schnitzel, gossip and scheme at the Tivoli, “an eating-place-cum-bar” just down the Nes, not far from the Authors Theatre where they rehearse. It feels a thrill to be back in the whirl, “to belong to it all once more.”2

But why him? Why “our Uli”?

The question haunts Mulisch’s novel, for reasons I will endeavour not to reveal here as ‘spoilers.’

It seems that the would-be director of a modern play —the plot of which interweaves with that of The Tempest— had happened upon a thirty-year-old photograph of Willem Bouwmeester in a flea market in Rotterdam one day. Captivated by the actor’s face, the would-be director had bought the photo for ten cents. “As soon as I saw your photograph I knew that one day I would do something with you,” the director later explained to Uli across a table in the Tivoli. And so it is that our octogenarian hero finds himself preparing for a leading role, and the part of the timeless magician Prospero to boot.3

Uli spends his first days back in Amsterdam in a reverie, transported by the rehearsals, lost in his memories. Not all of them easy. Uli responds by telling the stories his remembrances summon. He feels compelled not only to express but also, somehow, to try and explain himself and all that has befallen him. He is especially drawn to a cheerful and beautiful young actor named Stella, who happens to be playing both his love interest and Prospero’s daughter Miranda in their production.

Uli barely knows where to start amongst his new company, let alone with Stella. He begins increasingly to act and speak on impulse. And without hope of resolving all that he raises up from the depths.

“We know far more about the war than people knew at the time,” he ventures at one point.4

One pleasant summer day, “yielding to an impulse, he asked the property manager if he could borrow the ivory walking-stick. It wasn’t really allowed, but all right then.” Wandering for wandering’s sake, the stick tapping elegantly along, Uli finds himself at the Leidseplein, where he enters the City Theatre by a side door, open only because a group of people were leaving. In an upper rotunda, within a semi-circle of actor’s portraits, he finds himself face-to-face with a painting of his father, Louis Bouwmeester.

Uli and his walking-stick collapse into memories, into thought,

only to be roused by an attendant, telling him the theatre is closed,

listening to not a word of the explanation Uli launches,

beckoning him toward the stairs and exit.5

◇◇◇

ONE EVENING, ULI screws up enough courage to ask Stella to dinner.

Decades younger than him, with admirable plaits atop her head and a “pink-painted bicycle,” Stella lives near the zoo. After inquiring about what his sister might think, Stella accepts.

Although it occurs to Uli that he has scarcely enough money on him to buy even a simple meal for himself, “the discovery almost amused him — he’d have to see what happened.”

A sense of unreality mounts as the unlikely pair leave the other actors at the Tivoli and set out. Their “Amsterdam glittered in the night.”6

Stella knows a bistro in Rembrandtplein, but its tables are full. Aware of a spell that might be broken,

Uli casts about for an option. And there, “in a narrow side street he saw in neon letters the word OSIRIS, of which the first ‘I’ flickered on and off.”7

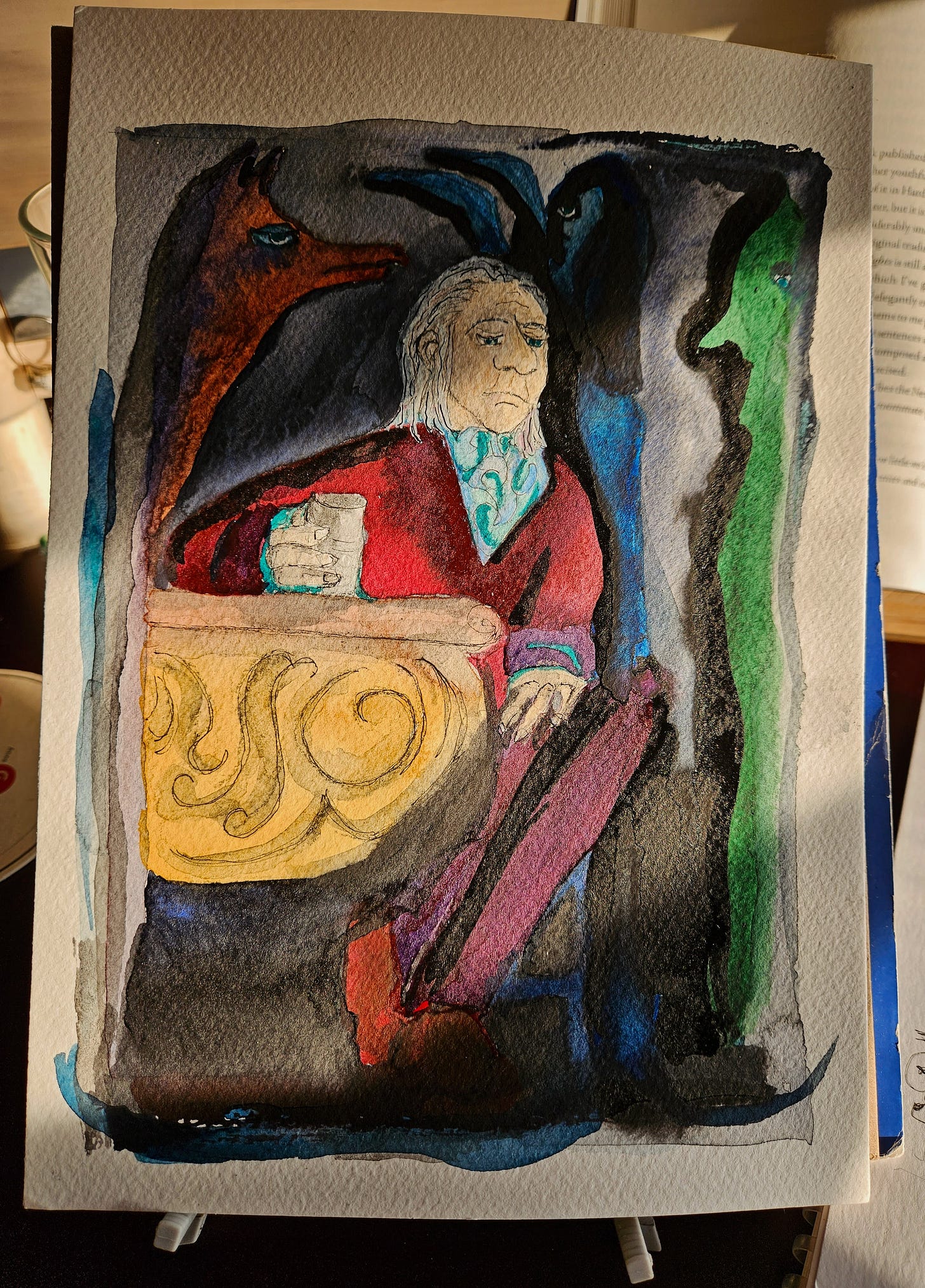

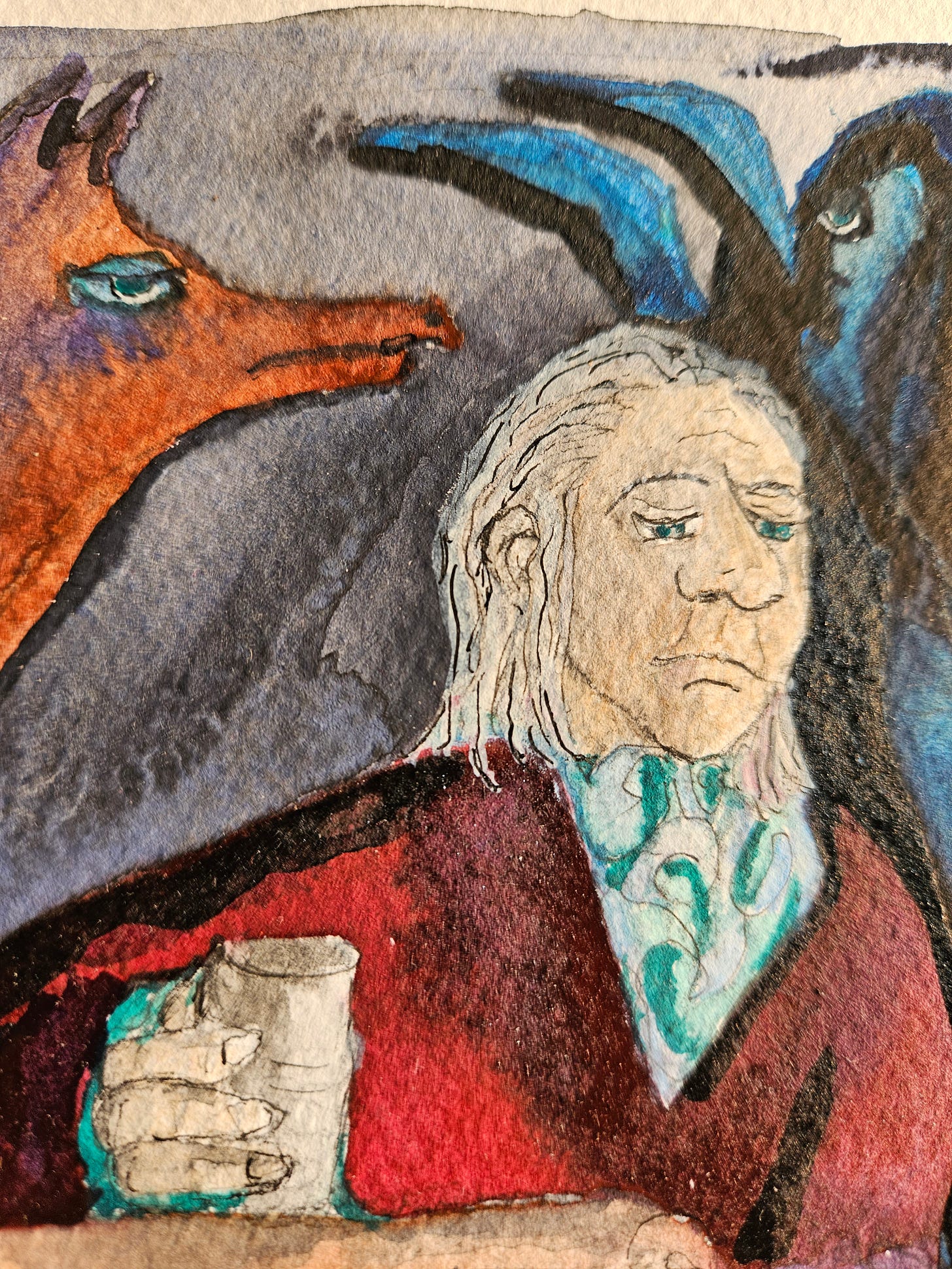

The restaurant is empty of custom, its soft music melancholy, the whole place “steeped in a profound twilight.” The walls are covered in fraying posters of pyramids, the Sphynx, and a golden Tutankhamun. There are hieroglyphs too, “on touristy brass,” from which also gleam an array of Egyptian gods, “half human, half animal.”

From “the bar, behind a balustrade and a stuffed crocodile,” a man gets up from a newspaper and his companion to light a candle and show them to a table. Things are looking up. The man has “the kind of warm smile born in sunshine that is unknown in the north," writes Mulisch.

Uli may have next to no money, but he cares less and less.

Fuelled by sweet wine and helpings of delicious food, the pair’s conversation careers every which way, taking in their rehearsals, his theatre memories, the purpose of art, what people will think about an eighteen-year-old woman dining with a man who is nearly eighty, and, before long, Stella’s upbringing. Things are going better than Uli might have dreamed until his tin of cigars reminds Stella of a wayward father and her heartbroken mother.

“Tell me,” he coaxes. If he has been learning one thing it is that “telling was salutary.”

Soon, as Stella prepares abruptly to take her leave, she brings out her chequebook and wants to pay. Remembering his situation, Uli hesitates, before waving her off “with an air of chivalry,” refusing even her second offer to go halves. Thanking him and insisting that she will pay next time, Stella asks, should we go?

“You go,” says Uli. “I’ll have a coffee and sit and think for a while.” He sees Stella off out the door, then “(tottering momentarily) . . .” he “looked at the two men … whose prisoner he now was, although they didn’t know it yet.”

He sits down, near a pleasantly beaked god, and orders another glass of Egyptian wine.

Before long a plate of sweet pastries appears. But Uli doesn’t notice.

He and his mind are off again:

Stella . . . this neighbourhood that he had begun to know some sixty years before . . .

That certain evening when Uli had been chaperoned, well before his time, by his flashy Uncle Karel . . .

All the things he should have told her.

* watercolours and photograph by Kenneth Mills

Last Call, trans. Adrienne Dixon (Penguin Books, [1985; in translation 1987] 1991), 65. Originally Hoogste Tijd (1985).

Last Call, 64, 59, 70.

Last Call, 28-30.

Last Call, 192-193.

Last Call, 133-137.

Last Call, 71, 65.

This and all following quotations are from the episode narrated by Mulisch in Last Call, at 72-80.

"If he has been learning one thing it is that “telling was salutary.” And if I have been learning anything since writing on Substack, I agree entirely. Salutary and a saving grace to some of us. Beautiful work, Kenneth and as always your watercolors are sublime. Do you ever offer your notebook paintings for sale? Or do you make prints? I would hang them all over my home.