The smell of freshly chipped potatoes deep-frying in a metal basket in the kitchen is everywhere. It's a Saturday evening in the mid-1970s. I'm set up, my papers and pens ready, on a TV tray table. This metal headquarters is collapsible, rickety from use, and one of six, each featuring a smudgy image of one of Canada's national parks.

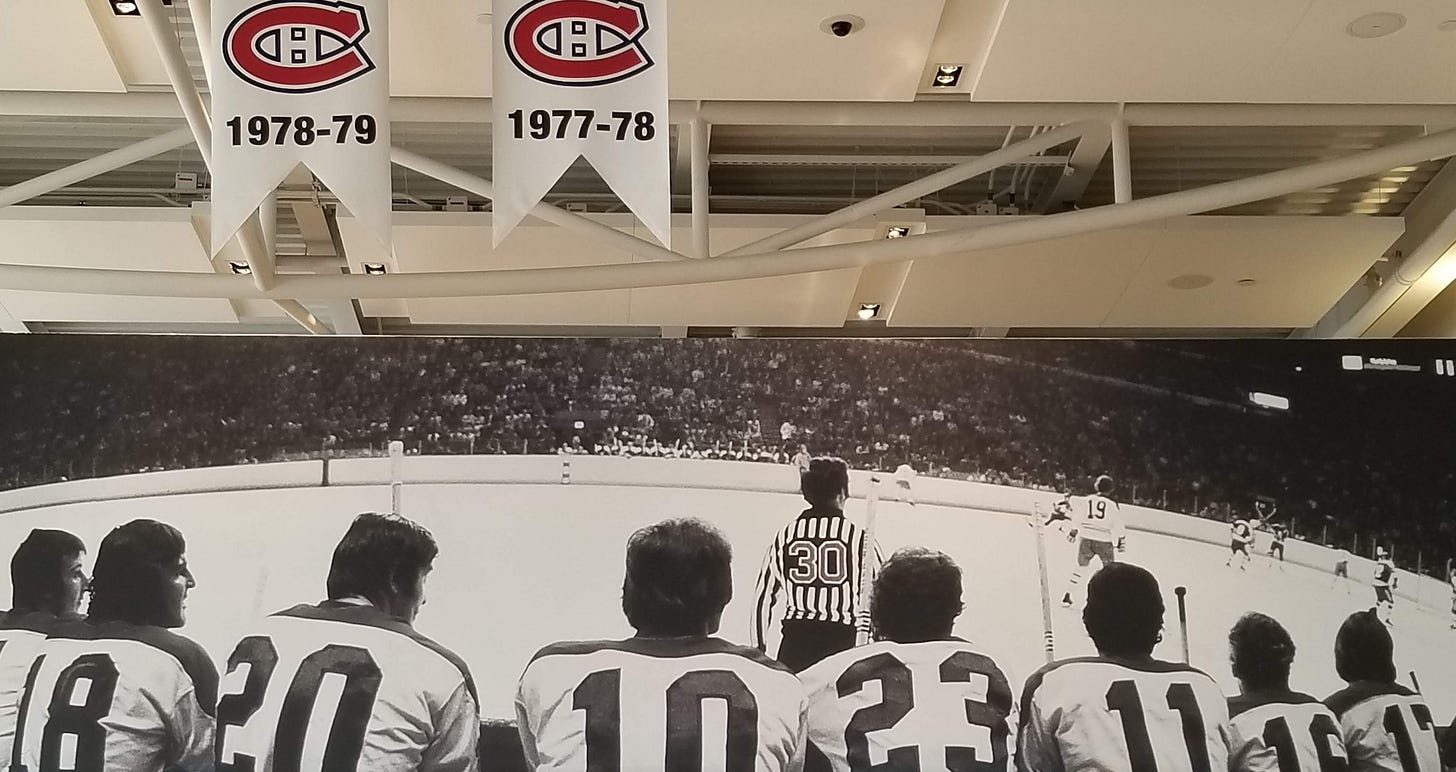

It's getting dark in the sunken living room, the flower-patterned couch casting its long shadow across the red shag carpet. The theme music for Hockey Night in Canada crackles from a small television atop a cabinet near a fireplace made of stones from the banks of the Red Deer River. Tonight's game isn't out of Toronto, thank god, but will beam from the fabled Forum in Montréal.

Another chance to see the Canadiens, my beloved "Habs," then coached (as if for eternity) by Scotty Bowman.[i]

My father's in charge of dinner. There's a beige telephone mounted on a wall to his left, which he lets ring and ring. A rare move in this day and age. He's watching over the chips, surrounded by dark-stained ash cupboards. Between them, through a window over the sink, in the waning light you can just make out the shape of the greenhouse, jutting out from the garage. The greenhouse gives on to the dimming outlines of a snow-covered field, a snaking, barbed wire fence and, way beyond, cloaked in shadow, a first stand of forest. Towering there is the silhouette of a tall tree, the one I climb to be alone, to get away from the squabbling, to read and think.

It's a “misty evening,” and James Joyce's character, the young Stephen Hero, is walking along Eccles Street in Dublin with all manner of “thoughts dancing the dance of unrest in his brain.” He chances upon a conversation, overhearing a “fragment of colloquy” between a young woman “standing on some steps” and a young man “leaning on the rusty railing." There was something about the exchange —its suggestiveness about lives, about pasts and possibilities— and he can't let it go. This "sudden spiritual manifestation . . . sets him composing,”[ii] then and thereafter, and offers a way of proceeding. Across Joyce's works are a series of [such] epiphanies," writes Theodore Spencer, "illustrations, intensifications, and enlargements . . . each "describing apparently trivial but actually crucial and revealing moments in the lives of different characters."[iii]

Joyce pluralised the notion of epiphany and took it to the streets, into broader human experience. It became "any showing forth of the mind by which . . . one gave oneself away," in the happy phrase of his fellow scribbler Oliver St. John Gogarty.[iv] The fascination reached such a point that during an "evening's dissipation" Gogarty recalls objecting when some "spark . . . or 'folk phrase'" suddenly quieted their friend Joyce and sent him from the table. Who's the latest "unwilling contributor. . . Which of us . . . ," Gogarty teases, has "endowed him with an 'Epiphany' and sent him to the lavatory to take it down?"[v] Not just the noticing, but the sifting and selecting and further discernment was begun as soon as possible. "To apprehend it," Joyce's fictional Stephen shares with his fellow-student Cranly about the common epiphany, " to apprehend it, you must lift it away from everything else." How wondrous it would be, he continues, to collect “many such moments together in a book of epiphanies."[vi]

At some point I'm allowed to eat right there, on the TV tray in the sunken living room. (My younger sisters, who preside over adjacent little worlds that overlap with my own, were actively lobbying for their own parental concessions!) The justification, in my case, is that I have to be at my station if I'm to follow the action. The pretext is that I'm keeping the game's statistics. I obtain a ruler. I etch headings above crooked columns on a piece of paper, leaving ample space below for the opposing team's records, the names of the offensive line-mates and defensive pairs for each side, not to mention the goal scorers, those who made assists, the penalties assessed for various infractions, any power-play or short-handed tallies, the lot. My stats may have been commended by my father, taking a break from the sizzling chips. But record-keeping is not my thing and it soon falls by the wayside.

It's by communing with these hockey broadcasts at the TV tray that I first leave the farm in Alberta for the big city. Travelling in my mind to such exotic locations as, well, Philadelphia and Chicago, Boston and Detroit. New York, where the Rangers play, is defined for me only by the CBC's footage of outlandishly-dressed people walking busy streets and yellow taxis weaving through traffic from Madison Square Garden. But what really fires my imagination, and draws my pen and colours, are the backstories to master and the continuing narratives to follow.

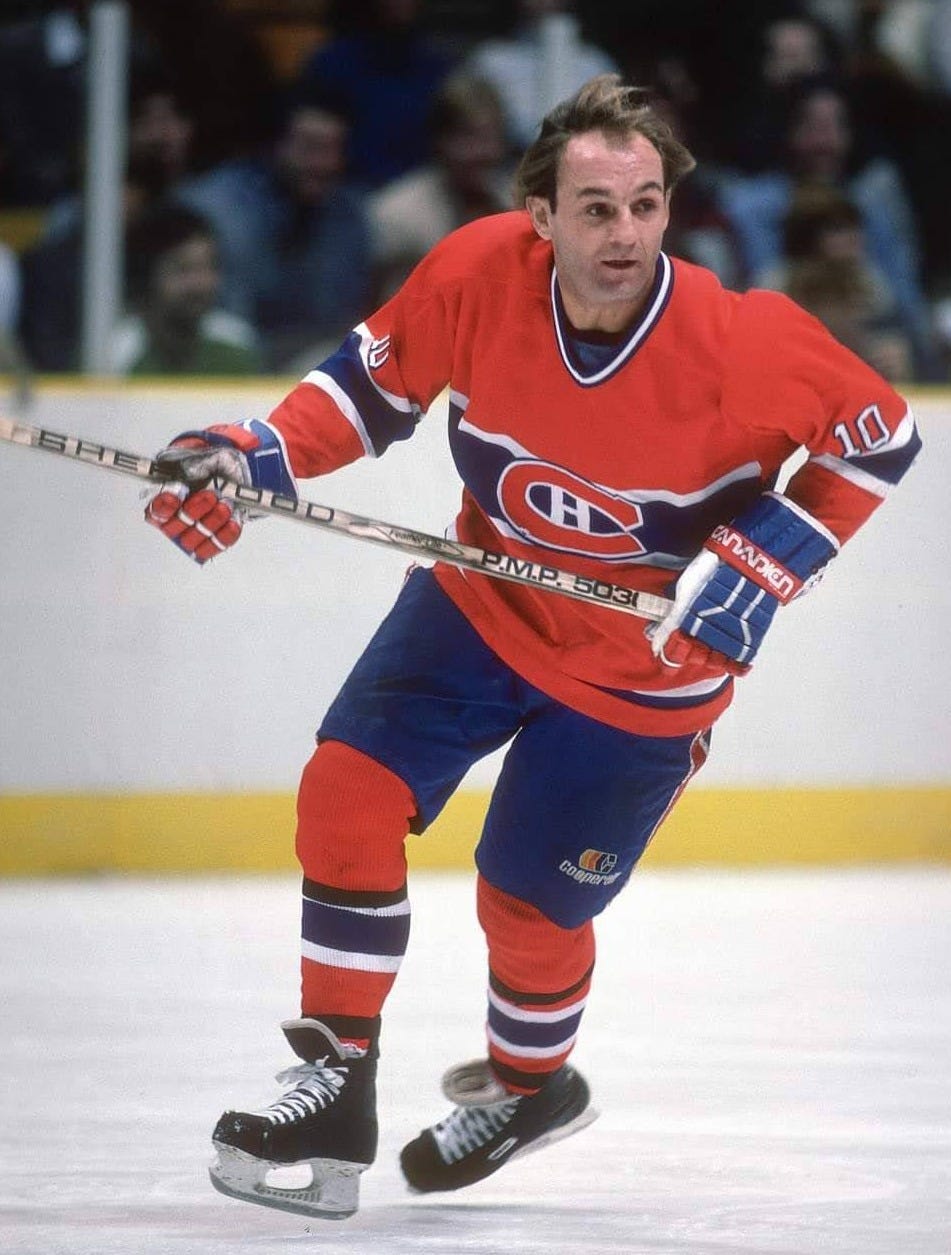

It begins on the ice, where so much happens quickly and there are big personalities to choose from. My favourite is the legendary winger Guy Lafleur,

whose number 10 I wear as a player whenever I can. His skates are already digging into the ice, and blonde mane flowing, as he wheels behind his own net

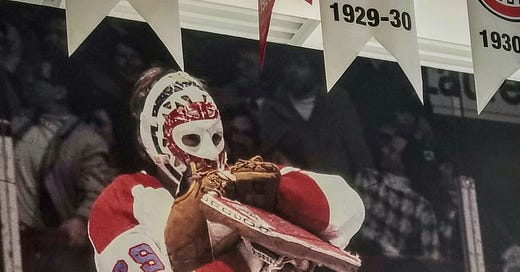

to collect the puck, winding up for an end-to-end rush. A close second is the giant goaltender Ken Dryden,

who (the commentators too frequently noted) had studied at Cornell University. And what about Henri "The Pocket Rocket" Richard, Yvon "The Roadrunner" Cournoyer, the great Larry Robinson ("Big Bird," and don't rile him up),

Guy LaPointe, or Serge Savard, who evades opponents with move that a silver-tongued Gallivan christens "the Savardian spin-o-rama." Contexts, like epithets matter, whether it's knowing about Robinson's long feud with the Bruins, Dryden's sore knee, or that Lafleur, for all his brilliance, is really only back in shape in time for the playoffs. What about the so-called "role-players," the "lunch-bucket brigade," the likes of Steve Shutt, Bob Gainey, Mario Tremblay, perhaps even Jacques Lemaire? They often make the difference, if not in every game but over the course of a season or long series, if not always through vision then from hard work. One of them will thwart an opponent's attack when the Habs' momentum has ebbed; another will steal the puck off two skaters in the corner, setting up the most unlikely of tying goals.

What happens off the ice —pre-game as much as in the aftermath— is compelling too. The games ask to be anticipated and to have their details chewed over. A promising match-up of supposed equals is different, for instance, than the golden opportunity for an underdog, which is distinct from the true test of the reigning champion or the current season's juggernaut. But how to break from the expected narrativising to form my own views while being bombarded (yes, even in this era before rampant egotistical bluster and sports-talk-radio), bombarded by the views of others? The biggest games are previewed by print-, radio- and television-journalists (who frequently disagree), and then framed and re-framed in situ. By on-air presenters and interviewers at ice-level, and by the play-by-play announcers and colour commentators who call the game from broadcast booths on high. I can still see them, the on-site crew, 70s slick with their flopping hair and sideburns,

in their matching baby-blue blazers with the puck-and-stick logo.

I align with certain kinds of scene-setting, story-telling, and synopses, kindling life-long aversions to others. Know-it-alls, briefly thrilling, are annoying, self-promoters earn their quick cull, imposters a discreet withdrawal from the action. Commentating legends such as Danny Gallivan and Dick Irvin Jr. (and Bob Cole and Dave Hodge), by contrast, are of a different order.1 They bring experience to bear, drawing old tales from the quiver to drive home a point. On the fly and during the intermissions that punctuate hockey's periods of play, these guys have time to zero-in. The stick-to-itiveness of an excellent forechecker (like a forward executing "the press" in football) rarely goes unrewarded for long. And, look, here's the player who "sees the ice," someone who's angled positioning is unlike everybody else, who foretells not only where his team-mates will be but also where space itself will open up. Watch unselfishness unfold, majestically. Chart the pass that leads to more.

Hear the commentators grow as suspicious of an early lead as they are of unfounded hopes for an operatic ending. The high-stakes gamble of the devil-may-care rushing defenseman will bring the crowd to its feet, but, look, he's given away the puck again; not everyone is Bobby Orr. They highlight one player's momentary loss of focus and another's susceptibility to a certain kind of applied pressure, and yet another's evident exhaustion: but, is he being over-played by a demanding coach or he over-stretching himself? They contrast those playing hockey for the sheer delight of the game to others who trudge along, as if mired in remorse or overburdened by their quest.

It's not that these hockey people (almost all of them men at this time) are objective, somehow suppressing home-sympathies —for the Habs, for the Leafs, even for the fledgling (from 1970) Canucks, for any team based in Canada— but, rather, that their remarkable subjectivities include observation, listening and persuasion. That they're elegantly fluid, complex interpreters of what's going on, reporting closely on what lies ahead and has transpired, including their own mistakes, their failures.

The TV tray table in the sunken living room on a wintry Saturday evening is a vantage, a figuring ground. It will beget its kind. From the kitchen window above the sink, looking past the greenhouse, on to the hayfield and trace of the fence, there's that tall tree. Which leads to the pasture further on, and, at the crest of a hill on its furthest edge, a particular cluster of fir trees breaking up the deciduous majority. The entrance of the place we call The Pretty Spot.

I crouch and crawl between branches, pausing as my eyes adjust to the sudden absence of light. I'm ushered inside and down to the creek by exposed roots, natural handles, into the soft dim, a realm of birds and squirrels and beavers. To a favoured seat on a smoothish piece of deadfall. Another set of tracks, another story.

Irvin and Gallivan, Cole and Hodge —like Foster Hewitt before them— are about more than television-in-its-adolescence for a kid on the farm. They're about more than ice hockey, more than voicing or watching a game. They usher in too, inventing words, singing out phrases. They unfold tellings that make me laugh and smile, and that, at the TV tray table, stir my pen.

"Don't go anywhere, my friends," it's Gallivan, "this one's far from over."

* “TV Tray” is a draft piece, in progress for a cherished working group, meeting next month. My thanks to Kris Lane for invaluable comments so far, and to Gregory Parker for timely encouragement on the frames.

[i] The professional ice hockey team, the Montréal Canadiens —le Club de hockey Canadien— are also known as "the Habs," short for les habitants, referring to the first colonists of French descent along the St Lawrence River in the region now known as Québec, as down quite another river to Louisiana in the south.

[ii] James Joyce, Stephen Hero. A part of the first draft of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, ed. Theodore Spencer (New York: New Directions, 1944), 210-211.

[iii] Spencer, "Introduction" to Stephen Hero, 16-17.

[iv] Oliver St. John Gogarty, As I was Going Down Sackville Street. A Phantasy in Fact (London: Rich & Cowan, 1937), 285.

[v] Gogarty, As I was Going, 285.

[vi] Joyce, Stephen Hero, 212, 211.

Footage featuring Danny Gallivan’s voice, and Dick Irvin, speaking in 2015, about his long-time partner on the broadcasts from Montréal.

I was a Bobby Orr fanboy, so i smiled seconds before you mentioned him, knowing that his name was about to come forth. Wonderful writing. Envious.

Really great stuff, Kenneth. The 70s hockey aesthetic is a thing. I saw Guy Lafleur play once at an exhibition game and remember the flowing locks. He was on the Nordiques at the time near the end of his career and they played the Great One’s kings of LA in Denver. Obviously, this was before the Quebec Nordiques became the Colorado Avalanche…now realizing this was incredible foreshadowing.